Poetry Fires the Revolution

High School

By Justin Sybenga

“Should I give more importance to the task of finishing my very important novel, or should I accept this dangerous job that the party assigns to me, the guerrilla, the frontlines, where I could lose not just a precious two months, but all the time I thought I had left?”

Roque Dalton, Salvadoran poet, 1969

There are such pressing unmet human needs that the artist must always wonder if creating beauty is the best use of his or her time and talent. For writers and artists coming of age in the middle of the 20th century in Central America, such questions weren’t theoretical.

More than 200,000 indigenous civilians were killed in the Guatemalan civil war from 1960-1996, many of them murdered by government forces. Eight business conglomerates controlled almost all the natural resources and wealth in El Salvador under the eye of military dictators, before civil war erupted in 1980 and a dozen years of terror and bloodshed ensued. The people of Nicaragua endured the brutal Somoza dictatorship from 1936-1972, prompting the Sandinista insurrection after the Managua earthquake in 1972, which killed 10,000 and left 500,000 homeless. The repressive governments that controlled Central America in this era were backed by the United States, whose companies were generating enormous profits from coffee and fruit exports and who ostensibly wanted to save the Western hemisphere from the threat of communism.

Images of starvation, homelessness, and brutal violence were impossible to avoid. A group of poet-activists formed in the 1950s calling themselves the “Committed Generation.” They dedicated themselves to fight for the rights of the poor and the oppressed, both through their writing and their political activism. Many of the greatest poets of the “Committed Generation” were jailed, exiled, or killed for denouncing the corruption and violence of the powerful and fighting on behalf of the common people.

In this series of three lessons, students will gain background knowledge on life in Central America during this volatile period in order to understand the risks these revolutionary poets took. They will read a series of poems by heroic Central American poets about the role of poetry in combatting injustice. Individually or in small groups, they will choose a poet to commemorate and will create a poster that includes biographical information about the poet and an image or metaphor about the power of poetry to change the world. These lessons can work well in English or Spanish classes. Spanish teachers could use the original Spanish poems rather than translations. There are many biographies available online in Spanish for the poets represented here, and students could create their commemorative posters in Spanish.

Essential Question

What power, if any, does poetry have in the face of war, oppression, and injustice?

Objectives

Students will be able to identify and analyze vivid images or metaphors about the role of poetry and social change.

Students will be able to commemorate how a poet from Central America used poetry and action in the fight for justice

Time and Materials

Three class periods

Clips from documentary Harvest of Empire or readings about Central American countries

Computers with internet access

Slideshow on “Apolitical Intellectuals” by Otto Rene Castillo (provided)

Set of poems about poetry by Central American poets with links to biographies (provided)

Student worksheet on imagery and metaphors (provided)

Commemorating a Poet assignment sheet (provided)

Lesson Activities

Choose a dozen or so quotes about poetry (here are a few resources) and post them on the walls, evenly spaced out, around your classroom. Feel free to find quotes from other resources that highlight other aspects of the power of poetry. Invite students to move silently about the room, reading each of the quotations. They should choose one that intrigues, pleases, or puzzles them and take a few minutes to journal about what it means before discussing as a class. Look for a natural segue into a conversation about poetry’s potential political power.

Tell students that they will be reading a number of poets from Central America, who stood against repressive military regimes in the mid 20th century. In order to sense the heroism of the Committed Generation, students must have an intellectual and emotional understanding of the violent conflict that raged through El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Honduras during this period. Students could watch the sections of the documentary Harvest of Empire, which highlight the political turmoil and US involvement in Guatemala (13:00 - 18:37), Nicaragua (54:38-1:02:15), and El Salvador (1:10:40 - 1:16:54). Alternatively, students could be divided into four groups, and each group could read an article about this period of history in Guatemala, Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador and report out to the class.

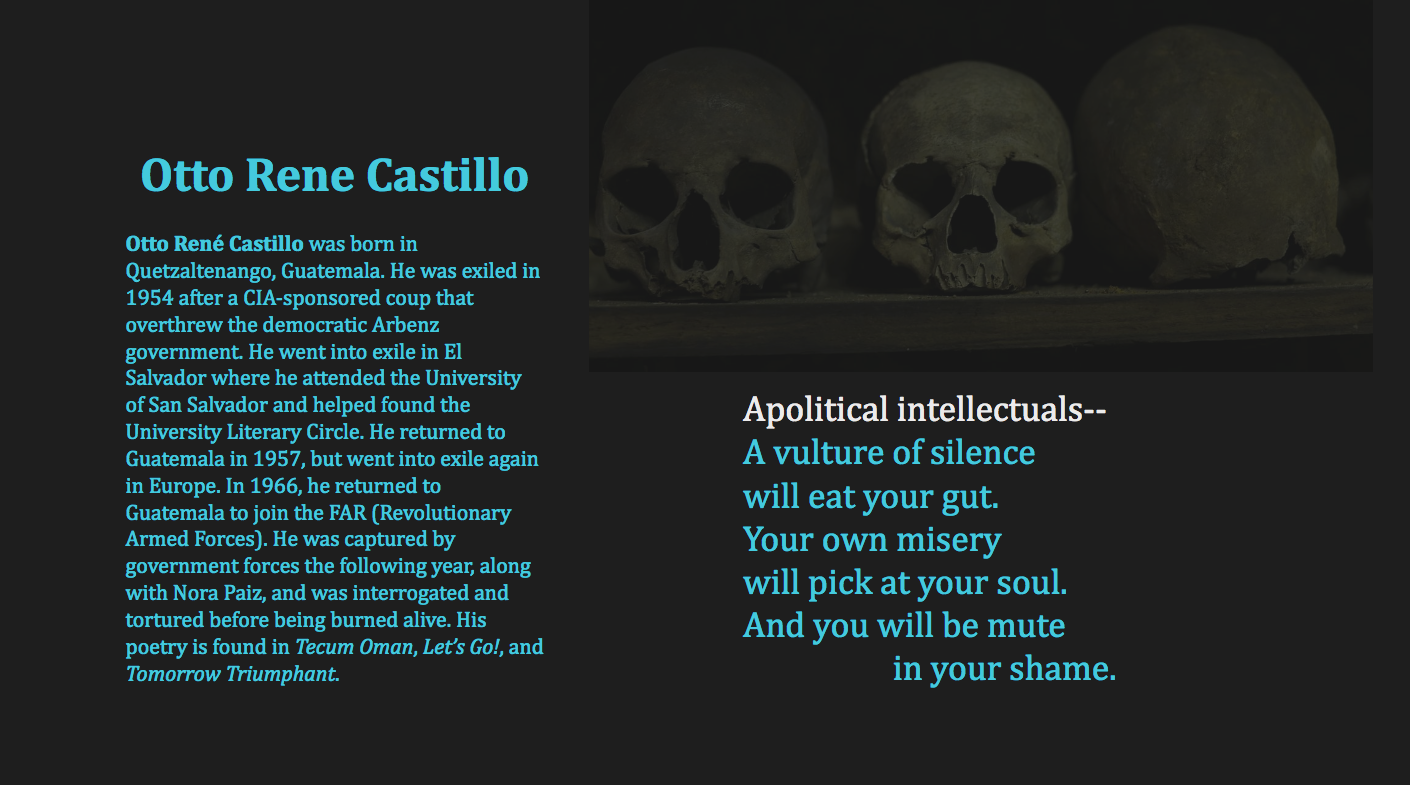

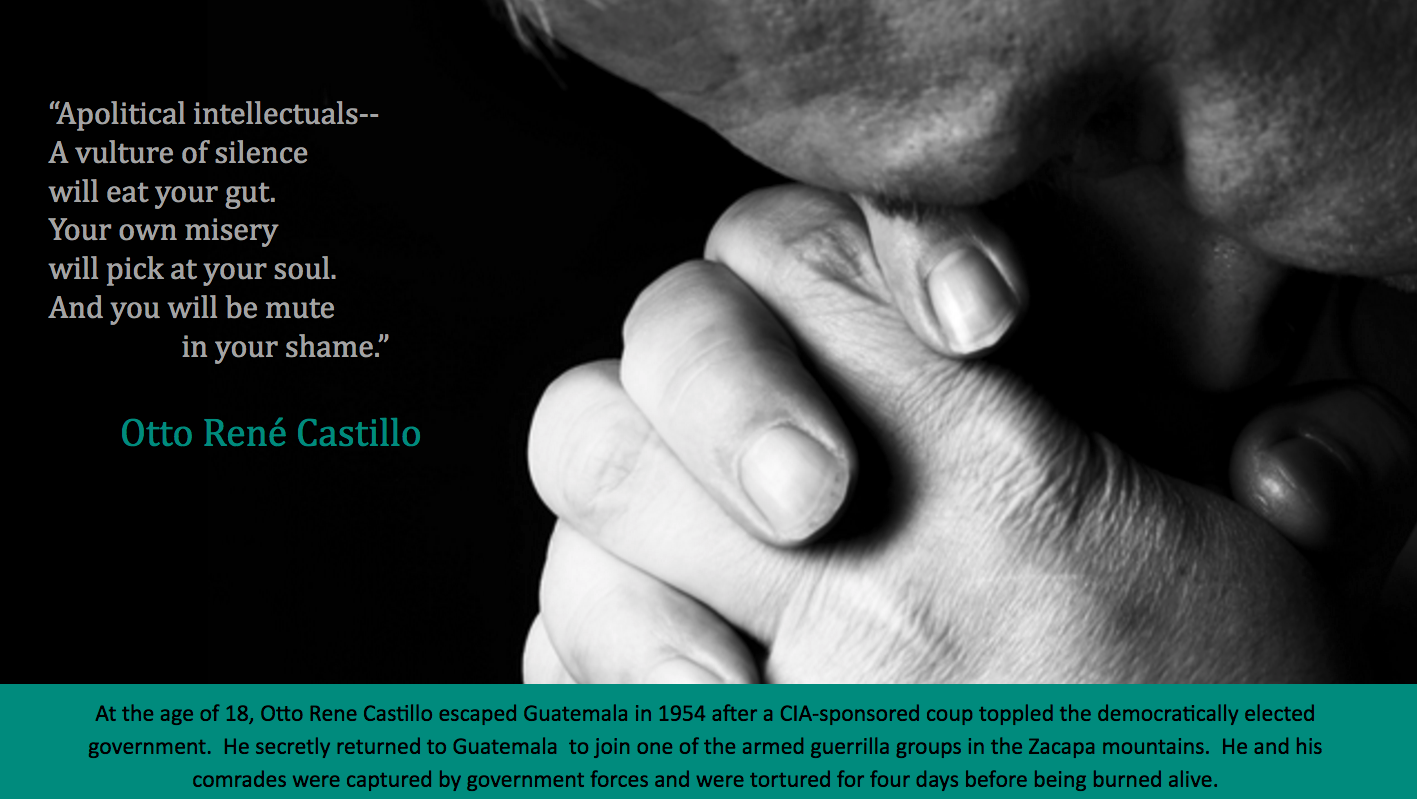

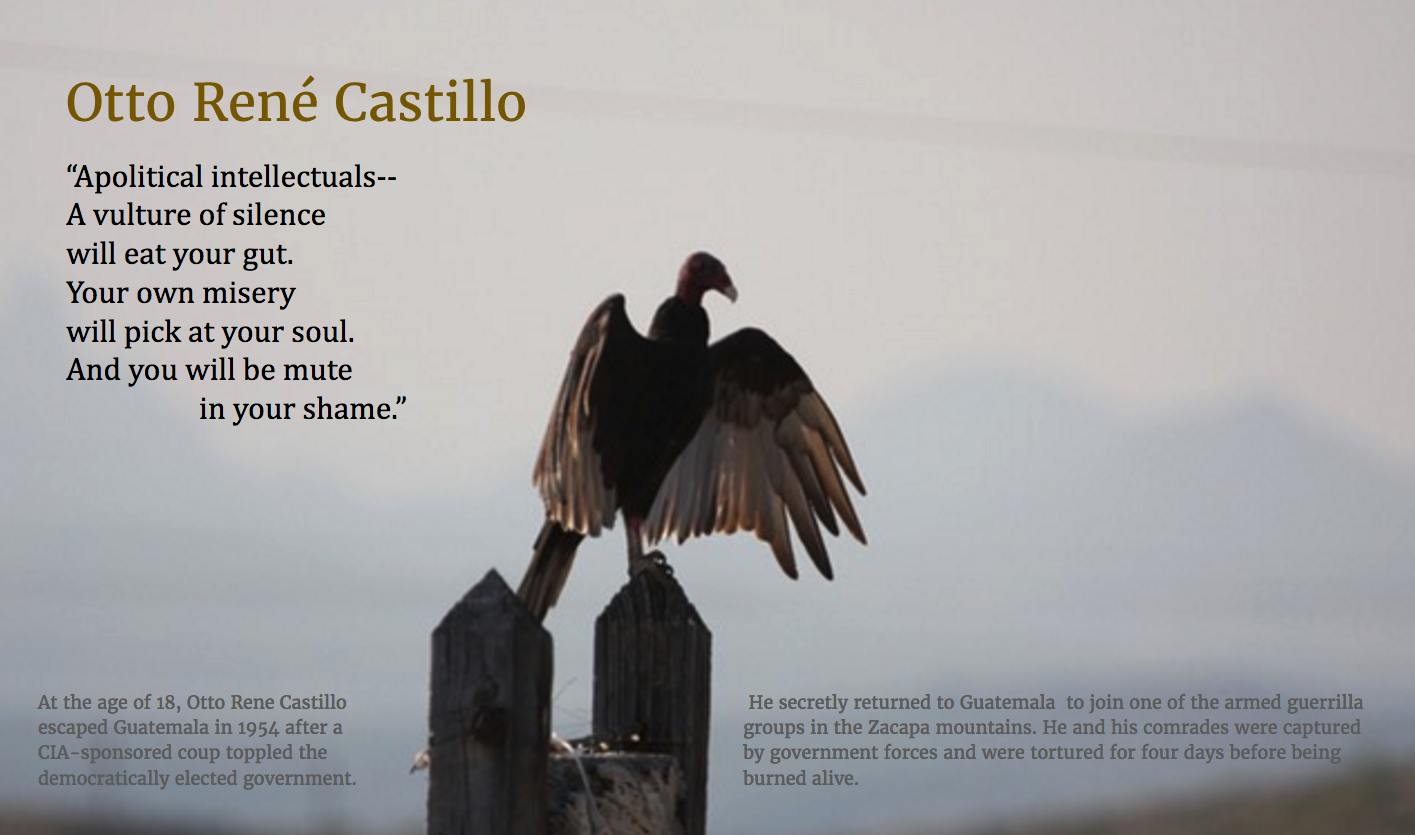

Poets and intellectuals had to decide whether to keep a detached distance from the events unfolding in their countries, or if they wanted to use their creative talents to lobby for social change. This lesson uses Otto Rene Castillo’s poem “Apolitical Intellectuals” to illustrate the choice between hiding safely in the academy or paying attention and empathizing with the suffering of others and risking everything to alleviate that suffering. The whole group analysis of this poem will serve as a model for the work students will do with other poems. Students will read the poem and identify and analyze images/metaphors that evoke ideas about the potential purposes of poetry. Then students will read a short biography to see how the poet’s beliefs were lived out. Finally, the teacher will show students models of the poster commemorating the poet that students will create for one of the other poets of the Committed Generation.

Briefly describe the emergence of the Committed Generation

Invite a student to read the biography of Otto Rene Castillo on the Teaching Central America website which is provided above the poem “Apolitical Intellectuals.” Discuss:

Why might have the government perceived Castillo as a threat?

Why might Castillo have been willing to sacrifice his home, safety, and his life?

Turn to the poem “Apolitical Intellectuals” and ask students what they think the title means. Political intellectuals are those who use their art and writing for activism -- whose artistic creations wake their audience up to see unfairness or exploitation in order to inspire political action and change. The prefix “a” means “not, absence, or without.” Based on Castillo’s biography, ask students to make inferences about what message Castillo might have for intellectuals who avoided politics.

Invite student volunteers to read each stanza of the poem aloud. Once they’ve experienced the entire poem, use the five W questions to clarify the basic storyline of the poem.

Tell students to reread the poem individually and to identify the images or metaphors that are most memorable. Have them share out some of the lines that stood out.

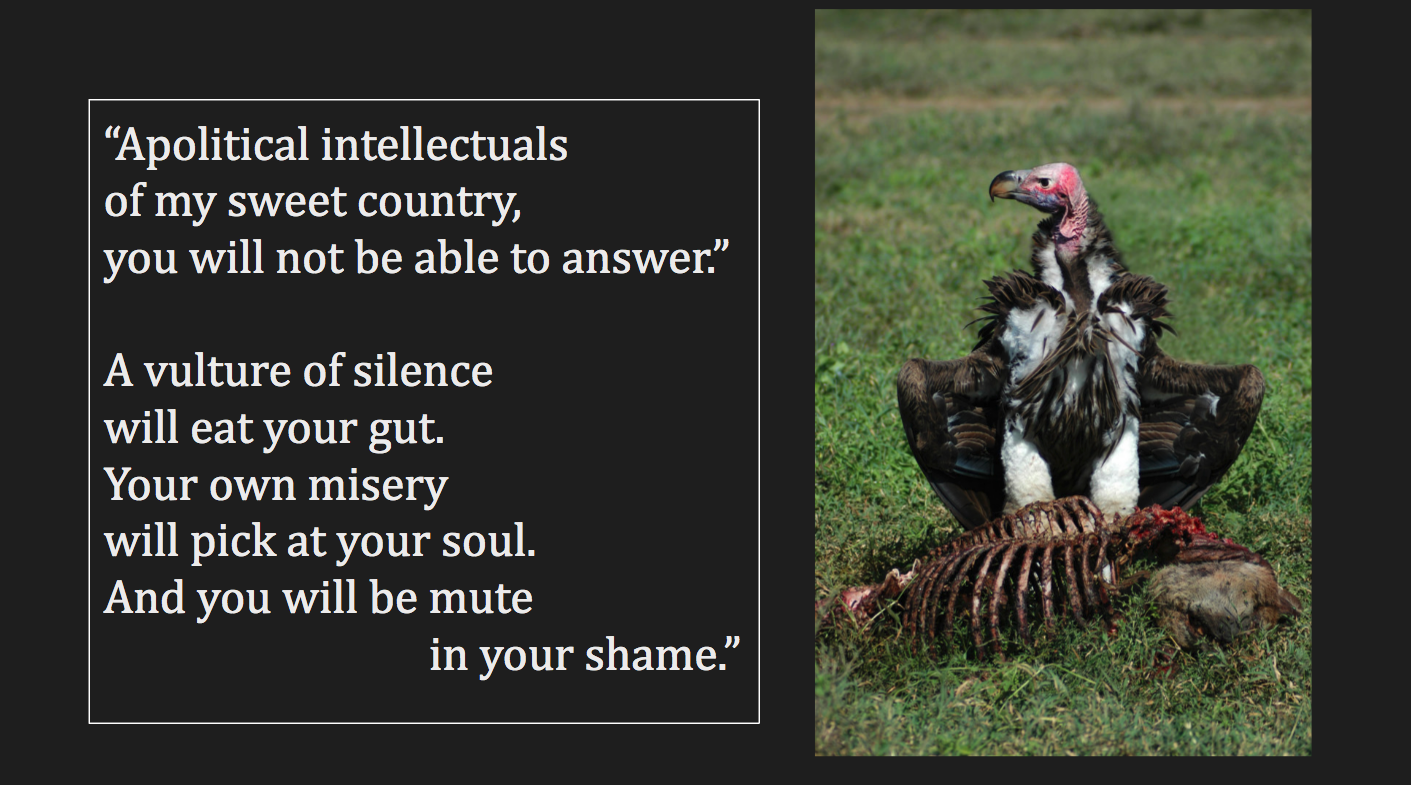

Use the slideshow to model for students how to tease out the associations and connections the poet is creating with the images and figures of speech. Students should take notes on the note-catcher, practicing for the independent work that will come later. An analysis guide is provided below to help move from the teacher modeling analysis for the first passage to drawing analysis from students through questioning. Commentary on the lines is also provided in the Google slideshow, in the notes section under the slide.

After analyzing the images and figures of speech in the poem, discuss the relationships between Castillo’s biography and this poem.

How was Castillo’s life similar to or different from the lives of the intellectuals he describes?

What does he hope that his political poetry can accomplish in contrast to the apolitical intellectuals’ work?

Is the end result of political poetry as evidenced by Castillo’s death and apolitical intellectualism the same or different? Why?

Click to the last three slides in the presentation and show students examples of commemorative posters that celebrate Otto Rene Castillo’s life and share a vision of what poetry could be from the poem “Apolitical Intellectuals.” Discuss with students how the selected images are more than a literal representation of a vulture picking at the poet’s soul. Rather, the image helps the audience sense the emptiness and shame that the intellectual feels for ignoring the suffering of his/her countrymen. Students will be creating similar posters to commemorate other poets of the Committed Generation.

- Students will work individually or with a partner to read a poem by one of the other poets from Central America and learn a little about the poet’s life. Seven poems, each which includes imagery and/or metaphors on the role of the poetry in the fight for justice, are provided along with links to biographies of the poet.

Teachers may invite students to browse through the poems and allow students select the poem that captures their imagination, or teachers may decide to assign each student/pair one of the poems to work with. More than one student/pair will work with each poem; when students are choosing which lines from the poem to feature in their posters, the teacher may encourage students to choose different images or metaphors.

Distribute the Commemorating a Poet assignment sheet and review the purpose, assignment expectations, process, and grading criteria with students.

Students should work in pairs or small groups with others who are reading the same poem to answer the reading questions, read the poet’s biographies, and analyze the images and figures of speech. Students can work individually or in pairs to write their own biographies and create their posters.

Posters can be completed on the computer using PowerPoint, Google slides, or a more advanced publishing program like PhotoShop. Students with an artistic bent may prefer to make an original drawing or painting to use as the background for their poster. Teachers can consult with art teachers at their school for support and access to supplies.

Teachers could decide to share resources about effective graphic design with students. Depending on interest and technological savvy, students will invest different amounts of time and energy into their graphic design, and that is OK.

Students will need guidance in choosing images to accompany the lines of poetry they have selected. At first, they may be likely to look for pictures that literally depict the object of the imagery or figure of speech. Use the following questions to prod students towards a more in depth analysis and more symbolic representation.

What characteristics or qualities does the object/thing described in the imagery or figure of speech have? Why does the poet highlight these qualities?

What emotions is the poet trying to evoke through the imagery or figurative language?

What message is the poet trying to communicate through the imagery or figurative language?

What image or images might help your audience to understand the poetic lines in a new or deeper way?

Once students have completed their posters, they should participate in peer feedback workshops, using the following questions. Before the peer feedback session, use these same questions to critique the sample posters featuring Otto René Castillo provided in the Google slideshow. Critiquing exemplars together in a respectful, honest way will create a safer space for students to provide kind, specific, helpful feedback for each other.

Is the text clear and concise and does the color and size make it easily readable?

How could the graphic designer use size, color, and spacing more effectively to focus the audience’s attention on the most important elements of the poster?

How can the choice of background color, font color and type, and the selection of image better match the mood of the poetry?

What new insight or understanding of the poetry does the image provoke? What other images might the graphic designer use to provoke deeper understanding?

Students should be given an opportunity to share their work once it is completed. Their posters could be displayed for a gallery walk in the classroom, displayed on a bulletin board in the school, or collected into a booklet for the classroom or school library.