History of El Salvador

Below is a brief overview of Salvadoran history up until the late 20th century. See also El Salvador: A Brief History, a booklet by David Iles available for free download.

Indigenous Population

Historians debate the origins of the first inhabitants of El Salvador. Some say they were Mayan, others say they were Aztec. However, it is known that the Olmecs lived and traded in the western provinces in about 2000 BC, as evidenced by the archaeological sites which include stepped-pyramid temples, ball courts and paved plazas.

In the eleventh century A.D., the nomadic Pipils migrated to El Salvador from Mexico and began an agrarian lifestyle similar to the Mayans. They called their new home “Cuscatlan” or “Land of the Jewels.” The Pipils were an eclectic people who learned to use both Aztec and Mayan calendars for agriculture and rituals, and performed complex mathematical computations in a base 20 number system which included the concept of "zero," a concept unknown to ancient Greeks and Romans. The Pipils were particularly skilled at crafts such as pottery, weaving, stone carving, and working with gold and silver. They farmed the land cooperatively, growing beans, pumpkins, chiles, avocados, elderberries, guavas, papayas, tomatoes, cocoa, cotton, tobacco, henequen, indigo, maguey, and corn.

The Pipil culture was influenced by the Maya. The Mayans developed a highly advanced culture organized around their agrarian way of life. They shared a profound respect for nature and sought to live harmoniously with their surroundings. Their gods embodied natural forces and phenomena, the most important of these being the life-giving Maize God.

The Pipils had laws to protect agriculture, social divisions, religion and the family. The death penalty was imposed on those who did not respect the gods, men who cheated on their wives, and thieves.

To help them in their farming and in their religious practice, the Mayans invented a highly accurate calendar which had a year of 365 days, broken down into 18 months of 20 days each, with five "hollow" or ill-omened days left over. The Mayans were also accomplished mathematicians and astronomers, who tracked planetary motion with great precision despite having no telescopes or docks. Mayans also communicated and traded with many other cultures, their merchants traveling to South America, Mexico, the Caribbean, and even Florida to exchange goods.

Perhaps the most obvious mark the Mayans made on the region is their great pyramids and planned cities, like the one Wilfredo visits.

The Pipils divided the territory into "cacicazgos" or kingdoms such as Izako, Apanecatl, Apastepl, Ixtepetl and Guacotecti.

The Invasion

The Pipils had been living in Cuzcatlan for over four hundred years when Pedro de Alvarado and his brother, Diego, invaded in 1524, close to the area which is now called La Hachadura. The Spanish invasion brought a fundamental change to the Indians' life. Shortly after their arrival, the Spanish began taking the land. They massacred the Pipils, destroyed their temples and gods, forced many into slavery and raped many women to provide pleasure and children for the invaders.

As the Spanish intentions became clear, the Pipils quickly adjusted from openly welcoming these strange and mysterious white people to actively trying to drive them away. Though they lacked the guns, cannons and horses of the Spaniards, the Pipils resisted the conquistadors for fifteen years. Historians estimate that in the first fifty years of Spanish conquest, the Indian population of El Salvador declined from as many as 500,000 to about 75,000 people. In addition to the massacres during the conquest, many died as a result of an illness which resulted from indigo cultivation. (See Catalina's Story)

A major historical theme had emerged in the life of the region which is still played out today: violent appropriation of large amounts of land by a heavily armed minority, and the continuing resistance of the dispossessed. Today in El Salvador, 4% of the people own 60% of the land, and 40% of people living in rural areas own no land at all.

Las Catorce

By the late 1800s, Las Catorce (fourteen families) controlled half the land in El Salvador. [Comparable to the 1% in the U.S.] This is when the "privatization" of the communal land of the Indians occurred. This was the basis of the coffee growing "oligarchy." In search of the greater profits to be made by exporting goods rather than by growing food for their fellow Salvadorans, the landowners focused production almost exclusively on coffee, sugar cane, and cotton. Where the Pipils had once harvested over 15 different crops to feed and clothe their own people, most of the land in El Salvador was now producing goods for people in other countries and for the profit of the oligarchy.

The intensive labor needed to grow and harvest these crops was supplied by peasants who no longer had enough land to support themselves, and thus needed the minuscule wage paid by large farms to help feed their families. (In El Salvador, it is still common for children to begin working when they are six or seven years old.) In addition, vagrancy laws made it a criminal offense not to work a portion of the year as a wage laborer. Thus, both economic and legal pressures were exerted to force peasants off their own land and under control of the ruling families.

In the 1920s, the price of coffee dropped steeply, threatening the oligarchs' export business. To make up for their loss of profits, the ruling families took over even more land from peasants and cut their workers' wages in half. Following elections in 1932, in which the government refused to seat elected members of the Communist Party, peasants organized a popular insurrection to demand better living and working conditions. Most of these peasants were part of the indigenous population. The government responded to the strike by massacring an estimated 30,000 people, or 4% of the population, in one week. This event became known as "La Matanza", or "The Massacre." The military government established following La Matanza went on to ban every vestige of indigenous culture, including language, traditional clothing, and music. To avoid further persecution and murder by government troops, the indigenous people began to hide all outward signs of their identity.

La Matanza and the military rule which followed set the political tone of the next several decades in El Salvador, as military dictators followed one another into the 1970s. During this period, many U.S. corporations including General Foods, Procter and Gamble, ESSO, Westinghouse, Kimberly-Clark, and Texas Instruments established operations in El Salvador to take advantage of the low wages and lack of labor protection laws. Besides the fact that profits were now flowing directly out of the country, these companies' interests often coincided with those of the oligarchs, serving to deepen the disparity of wealth. The U.S. government even got into the picture, providing the Salvadoran government aid directed toward s export production.

More than 30 years after La Matanza, the plight of the typical peasant in El Salvador had not improved, and in fact had grown worse, with even greater disparities in wealth and land distribution. In the 1960s there was a diversification of agriculture and increased industrialization. However the income of the majority remained below poverty level and there was very limited access to potable water, education, health care and full employment for a majority of the population.

The Popular Movement

In the 1970s, students, labor groups (among them, teachers were one of the strongest forces), community members and religious leaders organized to demand reforms to create a more equitable society. Twice progressive candidates were elected president (1972, 1977), yet due to fraudulent election procedures they were not installed in government.

Marches were organized, such as in 1975 when university students protested the $1.5 million spent on a Miss Universe pageant. The protesters were fired upon by the police, dozens were killed and "disappeared."

Right-wing death squads (who many consider to be military assignments out of uniform) began to target religious leaders, teachers, and community organizers. One of their slogans was, “Be a Patriot. Kill a Priest."

Students, teachers, ex-government officials, factory and farm workers, began establishing rural communities and engaging in armed resistance to the Salvadoran military. They called themselves the Farabundo Marti Front for National Liberation (FMLN), after the militant attorney who organized Salvadoran workers and peasants during the 1920s and was executed in Mantanza.

The FMLN sought a democratic government that includes all sectors of society. Before this could happen, political repression by police and military forces must stop. Therefore, one of their central demands was that people responsible for kidnappings and killings are prosecuted and convicted. Until this requirement was fulfilled, they refused to lay down their arms and leave themselves defenseless. On a broader scale, the FMLN supported programs for land reform and a mixed economy, and cooperated with many other political groups to try to influence the government to change.

The organizing of the FMLN meant that what were once just considered police matters now became full-fledged civil war. Increased resistance was answered by intensified repression.

While death squad activity continued, all-out war tactics were initiated. Between 1982 and 1987, the focus of the Salvadoran military’s war effort was the elimination of the FMLN “zones of control,” mostly through large-scale aerial bombardment. U.S. military advisors stated that residents of these zones are not civilians, but should be considered part of the guerilla opposition. In other words, one could be shot for living in the wrong neighborhood. The independent human rights group Americas Watch reported in 1985 that thousands of civilians were being killed in these attacks, which seemed designed to force people to leave their homes. Over a million Salvadorans fled to the United States, Honduras, and Mexico to escape the war, and up to half a million have been forced to move within the country. In all, one quarter of the people of El Salvador were forced to move for their safety.

Throughout the course of the 1980s, the Reagan and Bush Administrations' policies were to support the government of El Salvador and the military, in hopes that the "communist" FMLN would be defeated. Archbishop Romero wrote a letter to President Carter begging that aid be withheld. He stated that "the United States should understand that the Armed Forces' position is in favor of the oligarchy; it is repressive." Romero also spoke to the soldiers imploring that, “In the name of God, stop the repression.” A week later, on March 24, 1980, he was killed while saying mass.

On December 2 of that same year, three North American nuns and one layworker were raped, tortured, and killed (learn more). But the aid continued. During the 1980s, the U.S. sent an average of $1 million a day, primarily for the military. Despite all this assistance, El Salvador in the 1980s actually "developed backward."

On December 11, 1981, a U.S. trained and armed battalion entered the northern village of El Mozote, ostensbily to search for FMLN guerrillas. They found none. Nevertheless, they executed more than 800 civilians in what is now referred to as the El Mozote Massacre.

The U.S. government's political hope in the centrist Christian Democratic Party was dashed as the far-right ARENA party, led by death-squad commander Roberto D'Aubuisson, came to power in the 1989 elections. Militarily, the FMLN proved that it could not be defeated, and the government, with its failure to obtain a conviction in the November 1989 army murder of the six Jesuit priests and their coworkers, proved that it would not prosecute the military for human rights abuses.

The Jesuits and their co-workers are only a few of over 80,000 Salvadorans murdered since 1979. Both the U.S. Embassy and Amnesty International blame death squads within the Salvadoran military for the great majority of these murders. Death squads have especially targeted people working in organizations which demand land reform, increased educational services, and better working conditions.

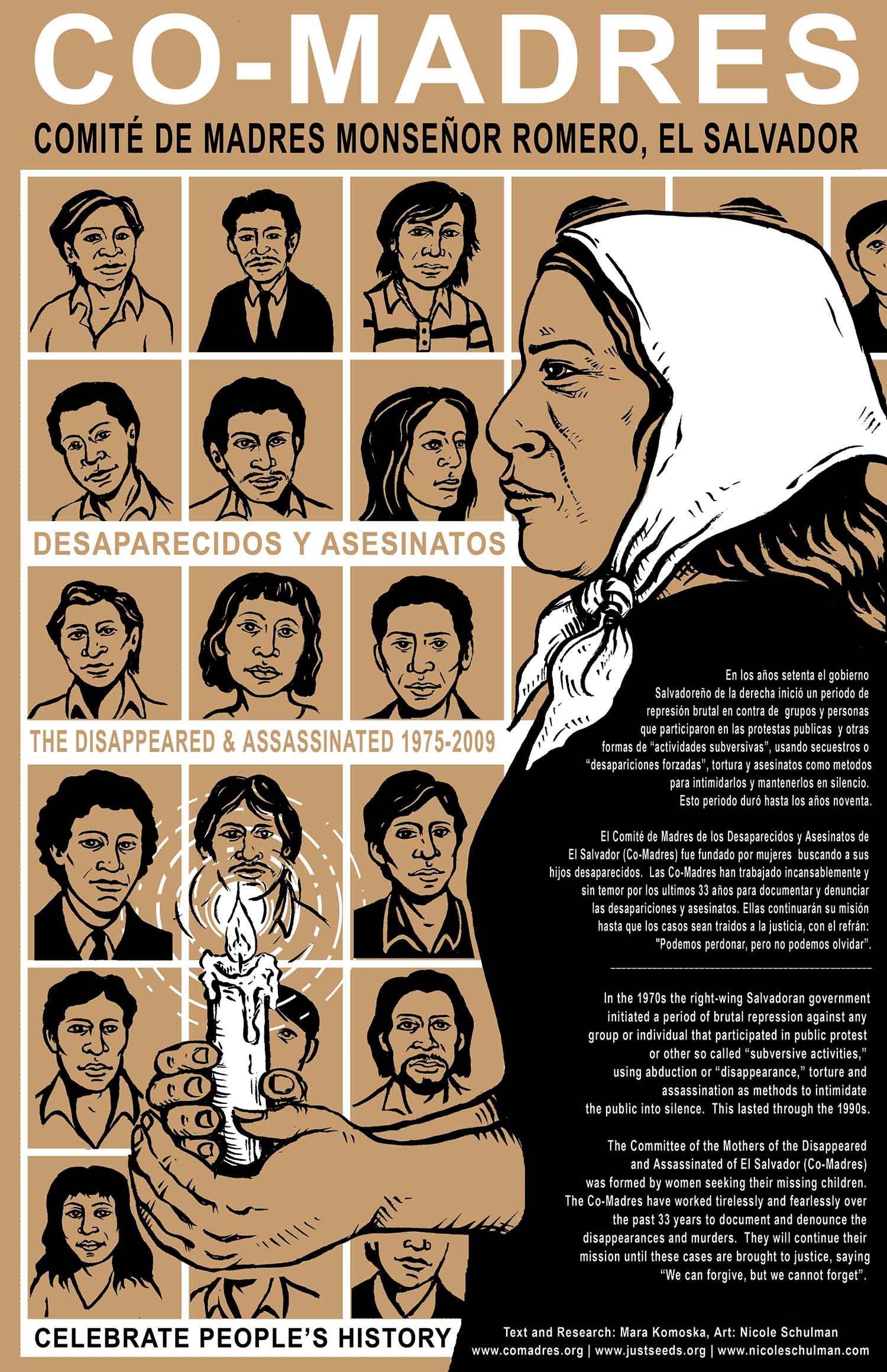

In 1981, after the assassination of El Salvador's Catholic Archbishop Oscar Romero, mothers of disappeared persons formed a committee in his name called the "Committee of Mothers and Families of the Political Prisoners, the Disappeared, and the Assassinated" (COMADRES). Many of them met while searching for their children and loved ones.

They brought their stories to the media, the U.S. Embassy, and to local and international human rights groups. They documented the numbers of disappearances and demanded an accounting of their family members, trials for those responsible, and an end to government complicity with the military. Many people in the United States campaigned to influence Congress to stop aid to El Salvador until the human rights abuses ended.

Although death squad kidnappings, torture, and killings are no longer at the levels of the early 1980s, they continue unabated. Kidnappings in San Salvador have become more selective, targeting popular leaders, particularly labor officials. In June 1986, the Los Angeles Times reported the kidnapping and beating of 11 different leaders of COMADRES and other human rights organizations by Salvadoran security forces. The six Jesuit priests murdered by the army in late 1989 were advocates of a dialogue between the government and the FMLN, and a negotiated solution to the war.

Arrests continue month after month, and many times the survival of those arrested depends upon timely pressure from people in this and other countries. Many Latin and North Americans work to inform people of human rights violations in Central America and try to build pressure on the governments to prosecute the violators and change the military.

Listen to oral histories of the Salvadoran civil war at the Unfinished Sentences Testimony Archive.

Refugees in the United States

Salvadorans who have moved to the U.S. to escape the war face many hardships even after they arrive here. Memories of the war, of loved ones who have been killed, and the experience of moving to a new country with a new language make adjusting to their new life difficult.

For children, this can be especially hard. A number of Salvadoran and Guatemalan students suffer from stressors related to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). People who suffer PTSD re-experience traumatic events in their lives in the form of memories and nightmares. PTSD was first noticed in the 1970s in Vietnam Veterans who had returned from the war.

Whether or not children have PTSD, they generally confront a combination of stressors including: reuniting with parents who may be unfamiliar to them, separation from grandparents and friends who may have stayed in their home country, memories of exposure to violence or abuse in their home country or during immigration, fear of deportation, health hazards, economic pressures, and discrimination. Often due to economic pressures, children have to cope with these stresses alone. Family, friends or the children themselves may be working in the evening, so rather than having an opportunity to debrief and rebuild their strength for the next day at school, the frustrations just build up inside.

Peer assistance and teachers who find activities in which the immigrant student can share their strengths and knowledge are critical.

There are many opportunities for teachers and students to get involved in efforts to both improve the life of refugees here in the U.S. and to end the conditions which force people to choose between their home and safety in the first place.

Credits

This history was adapted by Dan Farnham and Deborah Menkart from the following sources:

Armstrong, Robert, and Janet Shenk, El Salvador: The Face of Revolution. Boston: South End Press, 1982.

Barry, Tom, El Salvador: A Country Guide. Albuquerque: Interhemispheric Education Resource Center, 1990.

Burgos, Alfredo, Historia de El Salvador. San Salvador: Equipo Maiz, 1990.

Miles, Sara and Bob Ostertag, The U.S. and El Salvador: A Decade of Disaster. San Francisco: Institute for Food and Development Policy, 1989.

Further reading

El Salvador: 12 Years of Civil War. By the Center for Justice and Accountability.

Revista: El Salvador. In the Spring of 2016, the Harvard Review of Latin America dedicated a full issue of the journal to El Salvador. There are many invaluable articles on history, culture, and current events.